Friday, December 18, 2009

The Names of Hatshepsut as King

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

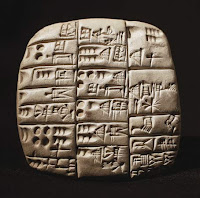

Tablet Project

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Excavation Project Update

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

Digging up Deborah

Thursday, October 29, 2009

On Boats and Sea Peoples

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Archaeology and Texts in the Ancient Near East

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

The Growth of Bureaucracy

The evolution of writing is something that has been debated for years, and while everyone can accept that its creation took place in Mesopotamia at the end of the fourth millennium B.C. there are conflicting ideas about how it began. The two theories are that writing evolved slowly over time or that it was invented quickly by a small number of individuals. Writing was originally intended for accounting purposes, and when looking at how accounts were tallied it becomes clear how writing could have evolved out of counting.

Writing was primarily used for bureaucratic functions at first, then gradually evolving into something that could be used to religious and historical writings. The first kind of record-keeping technology that was developed is a system of tokens. Tokens represented a quantity of goods that were hand molded out of clay or carved out of stone. They can be traced all the way back to the Neolithic period (around 8000 B.C.) and continue in use until around 3000 B.C. and were a part of a concrete numerical system.

The tokens were placed in clay envelopes called bullae that were approximately 5-7 centimeters in diameter and hollow in the center. One of the uses for bullae was that a certain amount of tokens could be placed inside and the bullae sealed. When sent along with an order of cloth or grain, the amount could be verified by breaking the bullae open and checking against the number of tokens. This gradually evolved into making impressions of tokens on the bullae’s surface, and then onto small tablets, thereby rendering the use of tokens unnecessary. This technology also brought about the use of seals in order to authenticate a tablet.

Stamp seals were the first form of seals developed and could identify the person, office or institution that the seal belonged to. They were typically carved out of stone or shell and were of one of two categories: naturalistic (hand-carved) or schematic (worked with drills). Interestingly enough, most seal impressions that have been found were of naturalistic type seals, while most of the seals themselves that have been found are of the schematic type. Also, the type of image on the seal can tell us something about who may have used the seal. Contest motifs are often associated with men, while images of two figures sitting and eating or drinking together are associated with women.

Stamp seals were the first form of seals developed and could identify the person, office or institution that the seal belonged to. They were typically carved out of stone or shell and were of one of two categories: naturalistic (hand-carved) or schematic (worked with drills). Interestingly enough, most seal impressions that have been found were of naturalistic type seals, while most of the seals themselves that have been found are of the schematic type. Also, the type of image on the seal can tell us something about who may have used the seal. Contest motifs are often associated with men, while images of two figures sitting and eating or drinking together are associated with women.

Friday, October 2, 2009

AIA Lecture #1: Underwater Archaeology

I have seen a few movies that portray underwater archaeology and I know that what we see in movies is more often than not a complete fabrication. Knowing that this is the case, I was surprised at how exciting the real life of an underwater archaeologist is. Listening to Eric Wartenweiler Smith, professional diver and underwater explorer, speak about his experiences in Egypt, the Philippines, Florida, and all over the world. Through out the talk, he spoke about the discovery of Cleopatra’s palace which he was involved in, the lost city of Heraklion, and shipwrecks all over the world.

I have seen a few movies that portray underwater archaeology and I know that what we see in movies is more often than not a complete fabrication. Knowing that this is the case, I was surprised at how exciting the real life of an underwater archaeologist is. Listening to Eric Wartenweiler Smith, professional diver and underwater explorer, speak about his experiences in Egypt, the Philippines, Florida, and all over the world. Through out the talk, he spoke about the discovery of Cleopatra’s palace which he was involved in, the lost city of Heraklion, and shipwrecks all over the world.  Most of the readings we have done in class and general knowledge about archaeology focus mainly on sites and artifacts found on land and under ground. But of course it seems obvious that over the years, through both shipwrecks and movement of the earth that a great number of artifacts are laying just beneath the waves. Taking Alexandria as an example, the movement of tectonic plates and gradual sinking of the sea floor has created a veritable treasure trove of artifacts. The sea floor is completely covered in amphora and in some areas not even 15 feet deep artifacts can be found that haven’t seen the surface in over 2,000 years.

Most of the readings we have done in class and general knowledge about archaeology focus mainly on sites and artifacts found on land and under ground. But of course it seems obvious that over the years, through both shipwrecks and movement of the earth that a great number of artifacts are laying just beneath the waves. Taking Alexandria as an example, the movement of tectonic plates and gradual sinking of the sea floor has created a veritable treasure trove of artifacts. The sea floor is completely covered in amphora and in some areas not even 15 feet deep artifacts can be found that haven’t seen the surface in over 2,000 years.Some of the most interesting things that Smith spoke about were new technology that has been developed to scan for underwater artifacts. Metal detectors, and submarines have long been used for underwater exploration, but as technology as progressed over the years, scanning has become more advanced and the use of computers has put most of the information into digital format. One of Smith’s most recent ventures is being a part of Aqua Survey Inc. a company that uses technology to develop better metal detectors and scanners. Their “mud sled” is able to find objects buried nearly four and half feet deep in clay. Not only can it be used for archaeology purposes, but also to find bombs and mines that were discarded over the years and can pose a threat to people and the environment.

I have never before wanted to try scuba diving, and really haven’t spent much time under the water, with the exception of a few snorkeling trips. Seeing how these divers worked and what they could accomplish for the first time made me curious about diving for the first time. Learning about all the equipment and techniques of salvage and restoration of the artifacts was interesting, as was learning about the risks of diving. I would never have guessed that statues had to be soaked in fresh water for years before they could be displayed. Division of goods and findings was also fascinating. To hear that in some countries they expect 50% of all findings and that others allow you to show the artifacts but return them to their native land created a whole new perception for me about treasure hunting and archaeology.

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

The Real Story of Nazi Eqyptology

I found the link to the article “The Real Story of Nazi Egyptology” on one of the Jack Sasson mailings. It interested me for many reasons but mainly that I had never thought of the Nazi’s interest in Egypt. Other than the Indiana Jones movies, mentioned in fact in this article, and my limited knowledge of the Nazi obsession with the Aryan race and looking for its origins, I had no idea that a great deal was done in the field of archaeology by the Nazis during the thirties and up until the end of the Second World War. The article is about Thomas Schneider, a professor at the University of British Columbia, who is in the process of examining this time in history and writing a manuscript.

Prior to the rise of Hitler, Germany had been known as a respected figure in Egyptology and even had an archaeological institute based in Cairo. Some famous figures in this field were Adolf Erman who helped to “unravel the grammar of Egyptian writing”, Ludwig Brochart who discovered the famous bust of Nefertiti, and Heinrich Schafer who made huge steps forward in understanding Egyptian art. Many American Egyptologists also trained in Germany, including the inspiration for Indiana Jones himself, James Henry Breasted.

One of Professor Schneider’s main points in this study is to show that the Nazis that were involved in archaeology during this time were in no way uniform in their studies or activities. One example is Helmut Berve, a professor or ancient history at University of Leipzig, who questioned the right of Egyptology to exist at all, saying that “Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Germany will automatically focus on the peoples akin to us in terms of race and mind; Egyptology and Assyriology will recede into the background,” transposing the ideals of Aryan thought into the study of the ancient world. Walther Wolf, another pro-Nazi Egyptologist who defended the study by saying that the ruling of Pharaoh can be likened to the way Hitler ruled over Germany and it’s conquests.

On the other side was anti-Nazi Alexander Scharff, who was one of the chairs of Egyptology at the University of Munich. He openly criticized Wolf’s work and contested that you could not use the “lens of Nazism” to critique or defend Egyptology because the two are completely unrelated. Despite his criticisms, he was actually able to keep his job throughout the war. George Steindorff was another prominent Egyptology professor, who also happened to be Jewish. He was forced to quit his positions and flee to America to escape from being placed in a concentration camp.

The Nazis also controlled the former German Archaeological Institute base, which operated until the beginning of the war in 1939. Professor Schneider believes that during that time, the Nazis used the base to advance themselves in the Middle East. The head of the institute, Hermann Junker, continued to excavate during the war and was a Nazi supporter. He focused most of his time excavating the Great Pyramids at Giza and worked primarily without direction from Hitler or any other Nazi officials. There is a lot of speculation, however that the base’s use was not confined to solely archaeological purposes, and that Junker often received Nazi guests and spread Nazi propaganda.

As far as the leader of the Nazis, Hitler, it is hard to say what is primary interest in Egyptology was. Professor Schneider did find a photo however of an Ancient Egyptian Art expedition in Berlin, 1938, with Hitler sitting in the front row. Hitler was also particularly interested in the bust of Nefertiti and refused to have it be returned to Cairo. In his great scheme for a transformed Berlin, Germania, Hitler planned to place the bust in a museum along side one of himself.

As Professor Schneider states, “This was, what I think, a decisive turning point in the international history of Egyptology,” and I after reading this piece I don’t think anyone could argue. Germany lost much of its academic credibility after this era, and lost some of its greatest contributors, such as Steindorff. This continues to affect Germany today and who knows what German academics could have accomplished had they not been disrupted by Nazism. It always surprises me how academic pursuits can be twisted and morphed into something entirely different by government or social influence. Especially after choosing to study Nefertiti for my excavation project, I am amazed at the history of her famous bust and Hitler’s fascination of it. I will most definitely have to look further into German Archaeology for that project, something I really hadn’t considered previously.

Thursday, September 17, 2009

Response Paper #2: How Were Artifacts Made, Used, and Distributed?

It seems simple to say that artifacts make up the bulk of discoveries by archaeologists, but when you consider how fragile and small some of these artifacts are, it is amazing that we have any record of them at all. What’s more amazing is to consider that these items were crafted long before the use of complicated manufacturing techniques with relatively primitive tools. In our quest to understand ancient peoples and how they lived, worked and died, it is very important to study these artifacts, how they were made and used and when they were created.

It seems simple to say that artifacts make up the bulk of discoveries by archaeologists, but when you consider how fragile and small some of these artifacts are, it is amazing that we have any record of them at all. What’s more amazing is to consider that these items were crafted long before the use of complicated manufacturing techniques with relatively primitive tools. In our quest to understand ancient peoples and how they lived, worked and died, it is very important to study these artifacts, how they were made and used and when they were created.An interesting point the author makes about artifacts prior to going into the rest of the chapter is that what we find may not be actually representative of how important the artifact was in the time of it’s use. One example is that during the Paleolithic period, most of the artifacts that have survived are made of stone, but there were most certainly tools made of wood and bone that were just as important. The author also expands on the knowledge we can gain by looking at artifacts. By using the artifacts to learn about the migration of goods and tools, we can make guesses about the trading habits of certain cultural groups, which lead us to know more about their economic systems and transportation.

As far as the types of artifacts found, there are two main classes – unaltered, such as flints, and synthetic, which were molded by human activity such as metal. The first recognizable tools were made out of stone around 2.5 million years ago and until the invention and widespread use of pottery, stone was the predominant material used. Through finding quarries and mines we can tell how the stone was removed and what kind of material was found. How tools were created also helps us to place them into a certain time period, as tooling methods evolved over time to become more efficient and complex. Another of the unaltered materials sometimes found is wood, although it takes a certain environment for the material to survive. Wood was a very important commodity for ancient cultures, and in fact many of the stone and bone tools made were for the harvesting of lumber. In a dry climate such as Egypt we have been able to find all sorts of materials that are wood-based including farming tools, furniture, toys, carpentry tools and even wooden ships. Waterlogged woods also can tell us much about woodworking techniques and how the artifacts were used. Plant and animal fibers are classified as unaltered materials but are very rare do to their fragile nature, especially from early periods.

Synthetic materials and their creation is strongly dependant on the use and control of fire, called pyrotechnology. The most important of these artifacts is clearly pottery, just due to the amount of it that has been discovered throughout the years and the differences that each culture puts into their clay work. From figurines to wine containers and bowls, almost every ancient culture produced pottery which also coincides with the settling down of cultures into villages and a more permanent lifestyle. Another prominent synthetic artifact is metal. The use of metals shows how human technique evolved over time, moving from working with copper and expanding to alloying and using bronze and other metals. Analyzing these artifacts in the lab allows us to see what kinds of metals were used and what techniques were employed in its creation.

While the article goes on to explain how these artifacts were used, I am more interested in their creation. What went through the creator’s mind when he first made a tool out of flint? These are some of the earliest pieces of evidence in the world of human discoveries that have affected the entire course of life afterwards. If that first person hadn’t created that tool or hadn’t figured out how to combine metals to create a stronger more durable metal then what could have been changed? It is so fascinating that these first tools have survived and we can still look at them today and see the creation of something new.

Thursday, September 10, 2009

Response Paper #1: What is the Ancient Near East?

While reading Marc Van De Mieroop’s A History of the Ancient Near East, I was surprised at how little I really understood about the Near East. Even the definition, something I had always assumed meant the Middle East or simply Mesopotamia, was not what I had expected going into this reading. Mieroop designates the Near East as “the region from the Aegean coast of Turkey to central Iran, and from Northern Anatolia to the Red Sea” and defining Mesopotamia as only a part of the Near East, abet the most important and documented of the areas (1).

I had also never considered that the evidence of past civilizations found in Mesopotamia and the surrounding areas was so important because written word had only recently been discovered (around 3000 BC), providing us with great amounts of evidence about how the people there lived and died. Writing in this area has survived in great numbers. From stone monuments documenting the achievements of kings to clay tablets, the preferred method of documentation in this area, have remained for us to find after all these years. Texts range from “the mundane receipt of a single sheep to literary works such as the Epic of Gilgamesh,” and due to the dry soil of the region, preservation was relatively easy (4). I had never thought about how this might contrast with other cultures that used papyrus and parchment, relatively fragile materials, and how this affects our understanding of the cultures.

Another point made by Mieroop is that we have “only scratched the surface” of the archeological sites in the Near East during the 150 or so years that excavation has been taking place. When I tend to think of areas in the Ancient world that are famous for their ruins or structures, I usually consider Egyptian, Roman and Greek first. While this may be a naive view, I tend to feel that many of the major discoveries in those areas have already been made, or are at least underway just due to the greater amount of traffic and archeological study in those areas that I have read about in the past. The Near East presents a whole new wealth of knowledge that I had never even thought about in much detail. If there are thousands of uncovered sites left to explore, what’s to say that some of the most important discoveries in mankind’s history aren’t still beneath the dirt?

Something that I had heard about, however, was how war and the gradual closing off of the Middle East to western scientists, let alone all westerners who weren’t there for military duty, had effected archeology in this area. Not just considering the sites left to be discovered, but the destruction and looting of artifacts from museums in Iraq and other areas that have gone through wars and the complete destruction of sites, whether deliberate or by accident. This is cultural information that will never be regained, something that is so terrible and unnecessary. This has forced archaeologists to move to different areas of the Near East, mainly to the outlying areas of northern Syria and southern Turkey. Just from my perspective, while it is great that we still have access to some areas, losing the “heartland of Mesopotamia” because of war and internal conflicts is such a loss. That cultural heritage is something everyone should be able to access to, or at least the experts of that field should be able to go and learn what they can from something that could be lost forever.

When I first signed up for this course, I really wasn’t sure what the Near East was going to entail. After reading this chapter, I have a more concrete idea and more insight in to the benefits and problems with researching and exploring this area. I also have a better understanding of what could be found and what its purpose might have been, for example the structures of homes and how their size, placement, and even shape show us what was going on at that time with family structure and cultural shifts. The simple shift to a more rectangular structure from the previous round hints at a new social hierarchy and the evolution of specialized rooms. Taking that into context and the fact that the Near East is the presumed start of many of societies greatest discoveries such as agriculture and irrigation makes this an area of great importance in studying the evolution of mankind. Mieroop states his most important opinion in the introduction as well, that the “ancient Near East provides us the first cultures in human history which true and detailed historical research can take place, ” once again outlining its importance to world history and proving this is a place worth knowing (7).