Thursday, October 29, 2009

On Boats and Sea Peoples

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Archaeology and Texts in the Ancient Near East

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

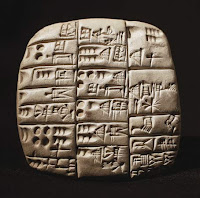

The Growth of Bureaucracy

The evolution of writing is something that has been debated for years, and while everyone can accept that its creation took place in Mesopotamia at the end of the fourth millennium B.C. there are conflicting ideas about how it began. The two theories are that writing evolved slowly over time or that it was invented quickly by a small number of individuals. Writing was originally intended for accounting purposes, and when looking at how accounts were tallied it becomes clear how writing could have evolved out of counting.

Writing was primarily used for bureaucratic functions at first, then gradually evolving into something that could be used to religious and historical writings. The first kind of record-keeping technology that was developed is a system of tokens. Tokens represented a quantity of goods that were hand molded out of clay or carved out of stone. They can be traced all the way back to the Neolithic period (around 8000 B.C.) and continue in use until around 3000 B.C. and were a part of a concrete numerical system.

The tokens were placed in clay envelopes called bullae that were approximately 5-7 centimeters in diameter and hollow in the center. One of the uses for bullae was that a certain amount of tokens could be placed inside and the bullae sealed. When sent along with an order of cloth or grain, the amount could be verified by breaking the bullae open and checking against the number of tokens. This gradually evolved into making impressions of tokens on the bullae’s surface, and then onto small tablets, thereby rendering the use of tokens unnecessary. This technology also brought about the use of seals in order to authenticate a tablet.

Stamp seals were the first form of seals developed and could identify the person, office or institution that the seal belonged to. They were typically carved out of stone or shell and were of one of two categories: naturalistic (hand-carved) or schematic (worked with drills). Interestingly enough, most seal impressions that have been found were of naturalistic type seals, while most of the seals themselves that have been found are of the schematic type. Also, the type of image on the seal can tell us something about who may have used the seal. Contest motifs are often associated with men, while images of two figures sitting and eating or drinking together are associated with women.

Stamp seals were the first form of seals developed and could identify the person, office or institution that the seal belonged to. They were typically carved out of stone or shell and were of one of two categories: naturalistic (hand-carved) or schematic (worked with drills). Interestingly enough, most seal impressions that have been found were of naturalistic type seals, while most of the seals themselves that have been found are of the schematic type. Also, the type of image on the seal can tell us something about who may have used the seal. Contest motifs are often associated with men, while images of two figures sitting and eating or drinking together are associated with women.

Friday, October 2, 2009

AIA Lecture #1: Underwater Archaeology

I have seen a few movies that portray underwater archaeology and I know that what we see in movies is more often than not a complete fabrication. Knowing that this is the case, I was surprised at how exciting the real life of an underwater archaeologist is. Listening to Eric Wartenweiler Smith, professional diver and underwater explorer, speak about his experiences in Egypt, the Philippines, Florida, and all over the world. Through out the talk, he spoke about the discovery of Cleopatra’s palace which he was involved in, the lost city of Heraklion, and shipwrecks all over the world.

I have seen a few movies that portray underwater archaeology and I know that what we see in movies is more often than not a complete fabrication. Knowing that this is the case, I was surprised at how exciting the real life of an underwater archaeologist is. Listening to Eric Wartenweiler Smith, professional diver and underwater explorer, speak about his experiences in Egypt, the Philippines, Florida, and all over the world. Through out the talk, he spoke about the discovery of Cleopatra’s palace which he was involved in, the lost city of Heraklion, and shipwrecks all over the world.  Most of the readings we have done in class and general knowledge about archaeology focus mainly on sites and artifacts found on land and under ground. But of course it seems obvious that over the years, through both shipwrecks and movement of the earth that a great number of artifacts are laying just beneath the waves. Taking Alexandria as an example, the movement of tectonic plates and gradual sinking of the sea floor has created a veritable treasure trove of artifacts. The sea floor is completely covered in amphora and in some areas not even 15 feet deep artifacts can be found that haven’t seen the surface in over 2,000 years.

Most of the readings we have done in class and general knowledge about archaeology focus mainly on sites and artifacts found on land and under ground. But of course it seems obvious that over the years, through both shipwrecks and movement of the earth that a great number of artifacts are laying just beneath the waves. Taking Alexandria as an example, the movement of tectonic plates and gradual sinking of the sea floor has created a veritable treasure trove of artifacts. The sea floor is completely covered in amphora and in some areas not even 15 feet deep artifacts can be found that haven’t seen the surface in over 2,000 years.Some of the most interesting things that Smith spoke about were new technology that has been developed to scan for underwater artifacts. Metal detectors, and submarines have long been used for underwater exploration, but as technology as progressed over the years, scanning has become more advanced and the use of computers has put most of the information into digital format. One of Smith’s most recent ventures is being a part of Aqua Survey Inc. a company that uses technology to develop better metal detectors and scanners. Their “mud sled” is able to find objects buried nearly four and half feet deep in clay. Not only can it be used for archaeology purposes, but also to find bombs and mines that were discarded over the years and can pose a threat to people and the environment.

I have never before wanted to try scuba diving, and really haven’t spent much time under the water, with the exception of a few snorkeling trips. Seeing how these divers worked and what they could accomplish for the first time made me curious about diving for the first time. Learning about all the equipment and techniques of salvage and restoration of the artifacts was interesting, as was learning about the risks of diving. I would never have guessed that statues had to be soaked in fresh water for years before they could be displayed. Division of goods and findings was also fascinating. To hear that in some countries they expect 50% of all findings and that others allow you to show the artifacts but return them to their native land created a whole new perception for me about treasure hunting and archaeology.